THE LATE „COMES”

Máté Hollós’ conversation with composer József Soproni

on his 24 preludes and fugues

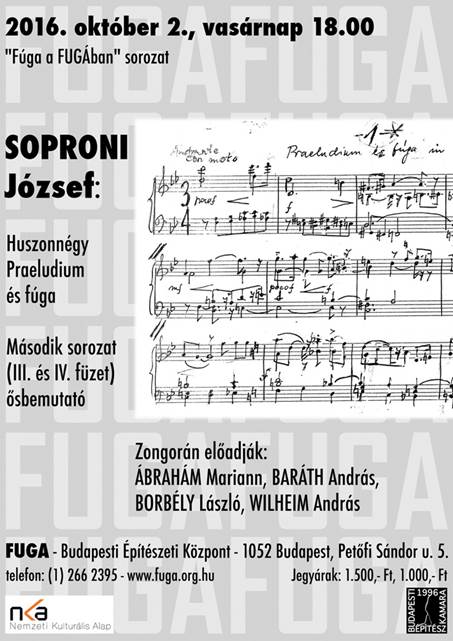

Twenty-four preludes and

fugues... Gigantic

undertaking. In the 20th

century only Shostakovich and György Geszler took on the challenge. In the 21st century József Soproni is the first to rise to it –

will anyone follow? He blazes his own

trail: he holds Shostakovich in high regard, but didn’t study his series in any

depth, and so far he didn’t look at Geszler’s work at all. In 2015 and 2016

four outstanding pianists: Mariann

Ábrahám, András Baráth, László Borbély and András Wilheim performed

the entire series at a live concert.

Three of them, Ábrahám, Baráth and Borbély now recorded on CD 18 pieces as homage to Soproni.

József Soproni, now 87, continues composing with the same ardor as

ever. I visited him in his home on Rózsadomb,

to talk about the cycle he wrote.

– We talked a lot about the pieces while I was composing – and he points

to his wife, Zsuzsa, a piano teacher. –

Her vast knowledge of music and professional sensibility is reassuring to

me. She perceives what’s behind the

music: does a given note make sense and if yes, what is it? She judges the form: isn’t something too

much, or too little? It is good that our musical tastes are identical.

– And do you accept her advice?

– Jóska ponders things a lot – interrupts him Zsuzsa. – He keeps thinking things over and over...

– And then I re-write them – continues

the composer. – I’m the biggest consumer

of manuscript paper...

– When did your close

connection to Bach start?

– I played a lot of inventions in the music school at the city of

Sopron. Later,

in the early 40s I started to play the organ in churches. Inheriting the role of Katalin Komlós’ father

I played at the student masses until 1947 – when they were banned. After being admitted to the Academy of Music,

as a pupil of János Viski, I composed 15 two-part and 15 three-part inventions

(unfortunately only the two-part inventions survived). [The curriculum required

only a few two-part and three-part pieces. – H. M.] That means I got very close to Bach from the

beginning, not only emotionally and intellectually, but also from the point of

view of the logic of music, of the method how the inner lines of force should

be kept alive. How the line progression

of parts unavoidably dictates one and only one specific note at a particular

location. I heard a couple of preludes

and fugues by Shostakovich performed by Tatiana Nikolayeva: they didn’t sound

baroque. They are serious compositions,

but nowhere near to Bach’s spirit. They

encouraged me to try to tell in my own way what does Bach mean to me. Writing the first 12 pieces was a two-year

process. I decided to ignore the

character difference of major and minor keys, since this would have narrowed my

latitude a lot. I didn’t start to

compose in the order of the circle of fifths.

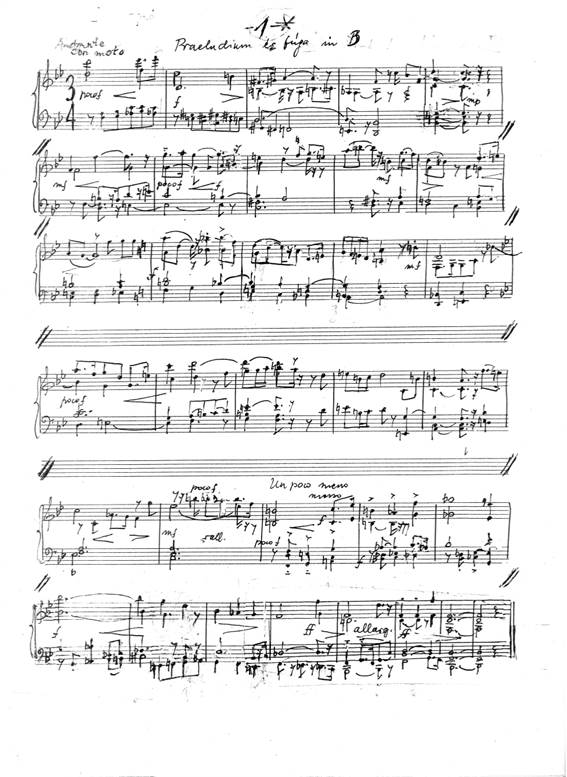

Given the great influence the Mass in B minor had on me I started with

the piece written in B. At the same

time, instead of a seven note scale I was thinking in terms of a six note

scale: the prelude and fugue in B was followed by D flat, E flat, F, G, A, then

I continued from B flat, C, D, E, F sharp and A flat. Although I didn’t use major and minor, the

tonality is dominated by the major.

Moreover, the cadence in general is an open, bright major, in both the

preludes and fugues. As an effect of the

whole tone scale I never write F and G after C, D and E, because it would

immediately imply the I.-IV.-V.-I. functionality;

instead, I jump to F sharp because the tritone enhances the tonal level. It provides a sense of elevation not only in

the melody, but in the bass, too. But

all this is not a theoretical concept, that’s how I hear it. The imitation doesn’t always start from the

fifth or fourth either; I remember how fresh it sounded when I started it from

the tritone. It’s a different

perspective.

– And how did the 12 preludes and

fugues turn into 24?

– I started all over again.

Having composed the series of 12 pieces and seeing that people began

performing them had a very positive effect on me. My inner drive kept me excited.

– When you used the same key for

the second time, did you reflect to the corresponding earlier piece?

– No!

– He barely remembered them

– adds his wife. – So much so, that

while getting ready for a surgery he kept repeating: I still have to write the

A flat! I had to put the piles of note

pages in order and in the process I found the prelude and fugue in A flat. Actually,

unusual for him, he even wrote on the page that he finished the piece in our

house at Zsennye. Mistakenly, he wrote

the pieces in G twice, too.

– Yes, and I rearranged the earlier one as a movement of my Sonata No. XXI.

– Listening to the

recordings I wondered what was more important to you: the spirit of the „fugue”

or „Bach’s” spirit?

– Bach’s spirit. Is that how you

felt?

– No question about it.

– More than that: I had Liszt, Schumann, Mendelssohn

on my mind, too. I played Mendelssohn’s

prelude and fugue in E minor back in music school. And Liszt’s B-A-C-H... Liszt was sort of a pretext for me. I felt the only way to face those

masterpieces is to chain them to myself. After all, how attractive the

atonality hidden is the B-A-C-H theme is!

– I remember when you called

our attention to this in your class on 20th century composing at the Academy of

Music.

– And this already leads to Bartók, to the fugue in the opening movement

of the Music for strings, percussion and celesta.

– Since you mentioned Bartók:

since Bach and the baroque there were quite a few developments in fugue

composition. Just to mention two

pinnacles: Beethoven and Bartók. Didn’t

they influence your preludes and fugues?

– Maybe Liszt, Schumann, obliviously. The construction of the fugue is

what attracted me.

– Now that the cycle of 24

is finished, do you feel that something is settled, complete in your oeuvre?

– This way of thinking is part of my life. In my 12 four-hand pieces that I just

finished I once again wrote a prelude and fugue. The latitude for the parts is much broader

there, but the material isn’t dense and care has to be taken that the hands of

the players don’t get in each others’ way.

– We already discussed your

fugues. As for your preludes, what was

your intent: how should they be different from each other and how should they

relate to the fugues?

– I didn’t relate them to each other, only to the respective fugues, to

establish the necessary contrast. In the

preludes I didn’t aim for figurative motions like the ones Bach applies. My goal was euphony and an intelligible

texture of musical sentences. I wanted

to make the cohesion points of the individual building blocks palpable. All my life I’ve been attracted by euphony –

in a broad sense – and wouldn’t have wanted to compose speculative music. I didn’t want to map a mechanized world. I tried it early on, I have shown it to Viski

back at the Academy of Music, but I chose a different path. I like to write music that one can follow.

– By now you have 21 piano

sonatas and 16 string quartets. How many

of them are still waiting for their first performance?

– The eighth quartet and all starting with the twelfth. Perhaps the Kruppa String Quartet will now

perform the XVIth, but in the meantime I already started thinking about the

seventeenth. There are quite a few

sonatas still in the drawer.

– Listening to your

responses it appears to me you don’t really care how many of them are still

unknown to the public.

– Sometimes I wish I could listen to my compositions, but alone, with no

one else hearing it. Then I would be

confronted with what should I have written differently. In any case, when I look back at my

compositions, it’s like going to a composition class to myself

– I’m dissecting them with the criticism of a teacher. But to answer your

question: there’s no longing for publicity in me.

– Alluding back to the

concepts of the fugue: József Soproni, late „comes” of „dux” Bach,

I wish that your compositions find their way to the public!

***

24 PRELUDES AND

FUGUES, I. and II. Series – Selection

József Soproni: Prelude and Fugue in B (I. Ser.) László Borbély, piano

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b8bGX3fH7_g

József Soproni: Prelude and Fugue in A flat (II. Ser.)

László Borbély, piano

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WRsuNrRyS_k

József Soproni: Prelude and Fugue in F sharp (II. Ser.)

Mariann Ábrahám, piano

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yLZt5W_Ysv8

József Soproni:

Prelude and Fugue in E (II. Ser.) András Baráth, piano

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jeqsl2Pz8Z8

József Soproni: Prelude and Fugue in D (II. Ser.)

László Borbély, piano

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OHT5IH7lkY4

József Soproni: Prelude and Fugue in B (II. Ser.)

András Baráth, piano

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-MBZHuiDSwU

József Soproni: Prelude and Fugue in A (II. Ser.)

András Baráth, piano

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u5T0FJuDNrs

József Soproni: Prelude and Fugue in G (II. Ser.)

Mariann Ábrahám, piano

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9Dm8drLKKu0

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=biNDgQWEXcI

József Soproni: Prelude and Fugue in F (II. Ser.)

László Borbély, piano

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3aJXlJgO67A

József Soproni: Prelude and Fugue in D flat (II. Ser.)

Mariann Ábrahám, piano

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kUkmHRaH9nc

József Soproni: Prelude and Fugue in D (I. Ser.) András Baráth, piano

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lPi5vlv40io

József Soproni: Prelude and Fugue in A (I. Ser.) László Borbély, piano

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=biNDgQWEXcI

József Soproni: Prelude and Fugue in G (I. Ser.) Mariann Ábrahám, piano

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_5jxN6HR2T4

József Soproni: Prelude and Fugue in E flat (I. Ser.) Mariann Ábrahám, piano

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HcKXz1D4rEs

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AIY8jDJfHJ0

József Soproni: Prelude and Fugue in A flat (I. Ser.) Mariann Ábrahám, piano

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a4L6ZRQsJH8

József Soproni: Prelude and Fugue in E (I. Ser.) András Baráth, piano

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V_vGv9q6EaI

József Soproni: Prelude and Fugue in C (I. Ser.) László Borbély, piano

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AIY8jDJfHJ0

József Soproni: Prelude and Fugue in B (I. Ser.) András Baráth, piano

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZnuK36iNqV0

József Soproni: Prelude and Fugue in H (I. Ser.) László Borbély, piano

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YrYIO4dlQdw

Fordította: dr. Dávid

Gábor

Translated by: dr.

Dávid Gábor

Dr. Dávid Gábor

T: 001-631-344-3016

david@bnl.gov

***

A interjú magyar nyelvű változata a

Parlando 2017/3. számában jelent meg:

A

késői comes. Hollós Máté

beszélgetése Soproni Józseffel 24 prelúdium és fúgája kapcsán